Introduction

Our system of government is a product of our history. There’s a rumour going around that our democracy comes from the Greeks. It might in Greece but in the Anglosphere it comes from the nordic peoples, the Greeks had nothing to do with it.

The history of modern Australia does not begin with Greece, Indigenous Australia, ANZAC Cove, or Federation. It begins with the Romans leaving Britain and the subsequent history of invasion and colonisation of that island. We begin our journey therefore in the British Isles, or as the Romans called them, Britannica. This part of the lesson is sourced from Cambridge Ancient histories.

Everyone Invades the Celts

Britannica south of Hadrian’s wall was first united as a Roman province. The Celts and Romans worshipped different gods and both were violent pagan societies. The Romans considered themselves to be civilised and were shocked at the Celtic practice of human sacrifice. The Romans sought to completely extinguish the druidic faith among their Celtic subjects. So effective was this campaign of cultural genocide that we know very little about Celtic paganism to this day.

However we do know that Christian missionaries arrived on the isles not long after Christ. They were Gauls whose descendants remain in Devon, Cornwall, Wales and Northern France. The early Celtic Christians had no knowledge of, or interest in, a Roman Vicar but worshipped Christ. Their priests married, were often self-supporting but also often lived in community with other Christian families called a Clas. It was these who brought Christianity to a pagan land and who held communities together after the Romans left Britton. There was no central legal or religious authority at this time and personal freedom and preference in matters of faith was the norm.

On the north sea shores of continental Europe a series of bad harvests and pressure from tribes in the east sparked emigration to Britain of Geats, Angles, Kents and Jutes from what is now Denmark and northern Germany. When these peoples set off to cross the North Sea the whole family sailed together with tools, weapons and farming stock all travelling in the same boat. It is from this that we get the word “fellowship” since they were travelling together in the same ship.

Things were also pretty tough in what is now Sweden. Many young Swedes from an area known as “Russlagen” sailed across to the opening of the large river systems and followed them as far as the Black Sea and the Bosphorous conquering and settling as they went. In the process they gave Russia its name deriving from Russlagen. The Norwegians or Norse went as far the United States but failed to make permanent settlements there. They did however begin to make permanent settlements in the north of what is now England and the Islands off the coast of what is now Scotland.

The Saxons were a Germanic people living on the Jutland peninsular in what is now northern Germany. They were first invited across to Britain by a local Celtoi Chief as mercenaries to help him in a local squabble. On finding a green and pleasant land they quickly invited their relatives and pretty soon a Saxon invasion began. The Saxons were effective colonists and the Celts were driven to the margins where the Saxons called them the “Welsh” which was a derogatory term indicating a group from which you would source slaves. This is the origin of Wales. Christianity still resided with the Celts but was pushed firmly to the margins. The Saxons at that time were pagan.

In the interim the Italian church had adopted the policy of having a single vicar or pope. This person sent a missionary called Augustin to convert the Angles and take over the Celtic church. This mission was largely successful and over time Celtic Christianity was absorbed into the Roman Church although some remained independent on the margins.

In the ninth century Celtic, Nordic and some Saxon kingdoms were generally religiously tolerant where lands were settled and a definite ruler was in charge. Our idea of multiculturalism and tolerance probably dates to this time as do some of our legal and political traditions. For example:

- Equality before the law was something practiced in Nordic societies at least among non-slaves. Similarly the idea that we are all created by God provides a moral basis for equality and the Celtic church did not have a rigid hierarchy. It is likely that the Celtic Christians and the Norse found a common value since neither society was highly stratified.

- Women were not regarded as property and had inheritance rights within Nordic society.

- The Nordic practice of electing 12 reputable men to hear and decide on disputes in a moot is the origin of our jury system. It was adopted by the Saxons and continues with us today.

- The Nordic peoples appointed a leader or King from a council of wealthy land owners/prominent men in the community. There was no hereditary kingship. Kings were ‘hands off’ in their ruler ship and were primarily military leaders who relied for their position on support from community leaders. Kings were expected to physically lead from the front.

- There was also a tradition known as a ‘wapentake’ which was a meeting of all arms bearing freemen to discuss and rule upon matters of interest to the general community. This was a primitive form of democracy that owes nothing to Athenian democracy or the Greeks. This is the origin of our Parliament and our notions of constitutional monarchy.

Britain at this time was a patchwork quilt of different tribes, languages, kingdoms, and faiths with ever changing boundaries and frequent armed raids from foreigners along the coasts.

Alfred Defeats the Danes

The Saxons had more regard for the religion and culture of continental Europe than they had for the conquered Celts or the pagan Danes and this led them to choose Roman Catholicism over the older religions.

In the year 870 AD Alfred became king of the Anglo-Saxons at a time of violent turmoil. Most of what we now call England had been overrun by Danish settlers who had invaded from the East. The Danes worshipped the ancient Norse gods of Odin, Thor et al who were gods of war. Odin’s symbol was the raven, a scavenging bird that followed armies into battle so it could eat the flesh of the fallen. Their heaven was Valhalla – hall of warriors, or the field of Freyja. According to their belief system, a Viking could only be assured that the Valkyries would carry their soul to Valhalla or the field of Freyja if they died in battle. This, and the desire for wealth and lands, led the Danes and other Norsemen on an extended rampage for most of the ninth century in which the normal procedure was to loot Christian monasteries and churches and burn them down, capture slaves and kill any who resisted. Their nearest equivalent today would be ISIS.

However in time they settled permanently and established a kingdom in East Anglia known as Danelaw under the rule of their king Guthrum. By 870 the Danes had pushed the Anglo-Saxons into the South and West corner of the Island. Alfred was now king of the last resisting overtly Christian kingdom and both he and his people were facing annihilation. That said; there were other Christian tribes on the Celtic fringes of the Island that had not been reached by the Danes.

For the next eight years Alfred fought the Danes and mostly lost, but the decisive battle took place in May 878. On the one side the Saxons gathered under their banner of the Christian cross. On the other side the Danes under their banner of the Raven.

By the end of the day the banner of the Raven had fallen, the Saxons were triumphant and the Danes were forced to surrender. As part of the terms of surrender Guthrum and his Chiefs converted to Roman Catholicism; receiving rights of baptism, and Alfred adopted Guthrum as his godson. This may seem strange but meant in effect that Guthrum became obliged to seek the peace of the two kingdoms and protect those Christians under his rule. A treaty formalising the two territories was completed two years later.

King Alfred sought to copy the hierarchy and organisational structure of the Roman Catholic Church in his kingdom. This was anti-democratic but it did bring stability and it would link his kingdom to powerful allies on the continent effectively brining it under the protection of the Pope. Having a highly organised faith would be a force for social unity. In short, it helped him to build a strong unified kingdom at a time when weak disunited kingdoms tended to get wiped off the map. His Danish rival Guthrum may well have beaten the Saxons if he had been able to unite his chiefs more effectively. However Alfred’s victory retarded the development of democratic traditions in England for two centuries. It paved the way for England to become a Roman Catholic country rather than a Nordic pagan or Celtic Christian one.

Key Points in the Cultural Origins of Democracy

- Celtic Christianity – no central authority, and freedom in matters of faith

- Nordic system – multi faith, multi racial, non-hereditary kings, concensus decision making, council of warriors/freemen make community decisions and elect king

- Nordic/Saxon moot – origins of jury system

- 400 years of Celtic Christianity in Britain before the introduction of Roman Catholicism

- Saxons invade Celts pushing them to the fringes

- Norse, Danes, Geats, Angles and Jutes invade Saxons

- Normans invade and conquer everyone except the Scotts – even the Romans left them alone.

Normans Defeat Everyone

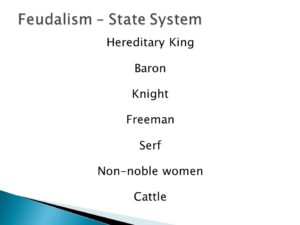

Roughly two centuries later in 1066 England would be again conquered, this time by the Normans. The Normans were a Nordic people who had settled in the north of France but there was nothing democratic about them. The Normans were Roman Catholic and practiced a form of absolute feudalism.

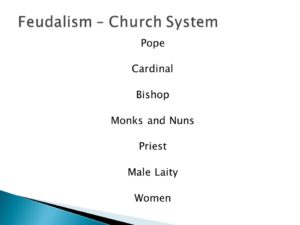

Under the feudal system the King was an absolute dictator and kingship was hereditary. A rigid social hierarchy was imposed in which your value as a human being depending on where you were pegged in the hierarchy. In simple terms peasant women were at the bottom with cattle, followed by peasant men, then local Lords, then Knights, then Barons who owned the castles and most of the land and wealth, then the King.

In the church there was the same hierarchy with women at the bottom, then laity, the priests, then Bishops, Archbishops, Cardinals and the Pope. Monastic organisations had their own place and internal hierarchies.

In England freedom and equality were buried but never wholly died.

England experienced a concerted attempt at religious reformation under Wycliffe in the mid to late 1300’s followed by the world’s first armed socialist revolution in 1382. This is known today as the ‘peasant’s revolt’. Indeed the history of England and the rest of Britain from 1066 to modern times has been about the struggle to regain and expand those freedoms that were lost to the Norman invasion and to the Saxon embrace of Roman (continental) Catholicism. It has been a 900 year project and it is still in progress.

Meanwhile England, once united under the Normans, went on to conquer the Celtic bits of the island to create Britain, and then went and conquered much of the rest of the planet.

Basic Conflicts Repeat

This basic conflict between local patriotism and integration with Europe, between local Protestantism and continental Catholicism, and between Parliament and the King, is the source of the constitutional history of both Britain and Australia. The desire for independence from Europe in matters political and religious, and the rivalry between the central part of England and the Celtic fringe, are still defining political issues in Britain today. As a result of these conflicts the British constitution still prohibits a Roman Catholic from being king or queen of England and provides that the monarch is also the head of the Church of England.

In Australia the Protestant/Catholic divide is of little relevance today. Rather the defining conflict is between the old religion of Judea Christianity and the new ‘religion’ of secular humanism, between the old ways of parliamentary democracy and the new rule of transnational corporations – what I call ‘the new feudalism’, between traditional notions of society, and the privatisation of humanity. These themes are explored further in this course.

A short diversion to the story: after defeating the Danes, Britain would later face annihilation by another group of people who believed in and worshipped Odin and the ancient Norse gods, and who sought to extinguish Christianity. That would be the Nazi’s who in 1940 threatened to overrun the Island. Hitler and the Nazi leadership were occultists and in many ways Britain’s conflict with Nazi Germany was a re-run of what happened in Alfred’s time.

Meanwhile a new religion has reached Britain and Australia that, like the old Viking religion, also teaches that you can only be assured of going to heaven to by dying in battle – that would be Islam.

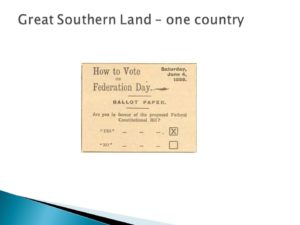

The English Find another Island

In 1788 a north Englishman called Captain Cook planted the Union Jack at Botany Bay and did not found Australia. He founded the colony of New South Wales. Other colonies followed, each one with separate laws, its own territory, and its own Governor reporting directly to Britain. In the late 1800’s the colonies decided to federate as a single country with a national parliament but with the English monarch as head of state, and with each colony having its own parliament and independent laws. Since no single colony had the power to form a country, Australia came into being by virtue of a British Act of Parliament which was called “The Constitution of Australia Act 1900” which created our constitution. This Act came into effect in 1901.

So in 1901 Australia became a country for the first time…a racially diverse but predominantly Anglo-Celtic nation with moral underpinnings from Christianity, some Nordic social values, and over eight centuries of social and legal development.

That is our heritage, that is where we have come from, and that is foundationally our identity. The critical difference is that Alfred sought to establish a Roman Catholic country whereas Australia is constitutionally Protestant. Whether Australia continues to be a culturally Anglo-Celtic Judeo Christian country will depend on the choices of this generation. However in order to make a choice we need to know our history back far enough to understand how we got to where we are.

Like Britain the great southern land has always been culturally diverse. Hundreds of languages were spoken here prior to European contact. However to the best of my knowledge and belief Indigenous people had no concept of Australia as a single entity. Rather we had many people groups, speaking many languages, and observing many customs.

The word ‘Australia’ means ‘southern’ and was used in different forms from the 1600’s onwards as a term for the great southern land. It was popularised by the navigator Matthew Flinders who was the first recorded person to circumnavigate the continent, and the term was officially accepted by the British Admiralty in 1824.

In 1824 ‘Australia’ was a place but not a country. It was more a collection of colonies surrounding a vast interior, but a sense of nationality was developing.

Historic photograph of the founding fathers of the Australian Constitution

Throughout the latter part of the 19th Century there was a sense that it would be better for the colonies to agree to form a national government to take care of common things like coinage, defence, postal service, and diplomatic relations and to that end a number of conventions were held to thrash out how that might work.

It is important to say here that the founding fathers (and they were all men) did not want to go down the American route and declare a republic. They considered themselves culturally British and remained loyal to the British monarch. Furthermore they wanted all the colonies to become States of the new Commonwealth. The States would keep their independence and have their own Parliaments and make their own laws, but they would hand over some of their powers to the new central government. The new central government is called the Commonwealth or Federal government.

So if you are going to have five State governments and a central Commonwealth or Federal government, you are going to have to have some rules about how all that is going to work …and that is what the Constitution of Australia does.

What you need to know about the constitution is this:

- Some powers belong to the Commonwealth and some powers belong to the States.

- Some powers are held by both but the Commonwealth has the say if laws are not consistent, that is, the Commonwealth prevails.

- The Constitution sets up the Federal Parliament, elections and the role of the Governor General.

- The Federal Parliament has two houses.

- House of Representatives is based on electorates with equal number of electors in them.

- The Senate has equal numbers representing each State. Its role is to protect the interests of the States and keep the national government in check.

- The British monarch is the head of State in Australia and is represented by the Governor-General.

- The Constitutions sets up the High Court of Australia.

- The High Court of Australia has the final say on interpreting the constitution.

The Governor-General has a number of ceremonial roles but importantly they also hold reserve powers as a head of state. So for example, if someone got into Federal Parliament and shot all our politicians, the Governor-General would take charge of the government, the Federal police and the armed forces, and issue writs for a new election. The same is true in Britain where the Queen is the head of the armed forces. Also if the Parliament becomes unworkable, the Governor-General can sack the Prime Minister and hold fresh elections; which is what took place in 1975.

Because the States have equal representation in the senate, a senate vote in a smaller State is worth more than a senate vote in a larger State. That is why smaller parties and independents base themselves in the smaller States and aim for the Senate because they need fewer votes to win a seat. The Democrats are based in South Australia. So is Family First, and now Nick Xenophon. The Greens are still largely based in Tasmania, as was Brian Harradine. Family First has also run a candidate in Tasmania. Therefore if you want to have influence a good place to start is with independent senate candidates and minor parties.

The Constitution of Australia Act also established the High Court as a final court of appeal and to rule on constitutional matters. So where does the High Court fit in? Well any Court in Australia can hear a constitutional matter. For example the local Magistrates Court once heard a case about abalone fishing that involved interpreting the constitution. However matters requiring a decision about how to interpret the constitution are normally heard in the High Court because that is the court of final appeal in Australia. The Court can sit anywhere but it is normally housed in a big building at the end of Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra.

Summary

We have swept through over a thousand years of history in ten pages.

We learned that our democratic traditions are Nordic in origin but were buried under feudalism that was imported and imposed from continental Europe.

We learned that Celtic Christianity in Britain was taken over by Roman Catholicism but the spirit of religious and political independence never died.

We learned about our origin as a multi-racial but predominantly Anglo Saxon Celtic nation.

We learned that Australia came about through the different colonies agreeing to form a central government that is still connected to the British Monarchy.

We learned that the written constitution of Australia sets up the Federal Parliament and the High Court of Australia, and sets out the rules about how the federation works.

In our next lesson we will explore what rights and freedoms we have under our constitution. Do we really have a right to free speech, freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, and freedom from governmental tyranny?…and if so, where do these freedoms come from?

Questions to Consider:

- How might our civilisation be different if Guthrum had won?

- Are there limits to multiculturalism?

- Alfred allied with the (Holy) Roman Empire. Historically Australia has allied with the British Empire and the United States. Have our links to powerful allies made us stronger or weaker? Are we more secure or less?

- Britain is an island off the coast of Europe. Australia is an island at the bottom of Asia. Both have been colonised by different people groups at different times. What does that tell us about the future?

Materials

Sources and References

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_the_Great

See also: Cambridge Ancient Histories

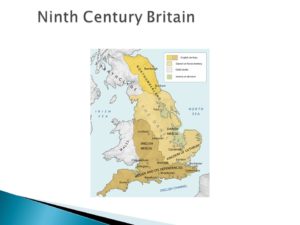

In Alfred’s time there was no such thing as “England” or “Britain”. What is now the UK was divided into several kingoms. The largest was the Saxon kingdom of Mercia but most of this had fallen to the Danes and only the West Saxon kingdom of Wessex remained. See the map below.

A map of Britain in 878, when Alfred was King of Wessex, showing the Anglo-Saxon and Danish territories. At one point, all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms bar Alfred’s Wessex, the most powerful, had fallen to the Danes

Picture source: http://forums.canadiancontent.net/history/121459-museum-remains-inside-box-thought.html

For additional maps see here: http://www.anglo-saxons.net/hwaet/?do=show&page=Maps

In April 871, Alfred came to the throne of Wessex and the burden of its defence ….the Danes defeated the Saxon army in his absence at an unnamed spot, and then again in his presence at Wilton in May. The defeat at Wilton smashed any remaining hope that Alfred could drive the invaders from his kingdom. He was forced instead to make peace with them, according to sources that do not tell what the terms of the peace were. Bishop Asser claimed that the ‘pagans’ agreed to vacate the realm and made good their promise.

Indeed, the Viking army did withdraw from Reading in the autumn of 871 to take up winter quarters in Mercian London. Although not mentioned by Asser or by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Alfred probably also paid the Vikings cash to leave, much as the Mercians were to do in the following year. Hoards dating to the Viking occupation of London in 871/2 have been excavated at Croydon, Gravesend, and Waterloo Bridge. These finds hint at the cost involved in making peace with the Vikings. For the next five years, the Danes occupied other parts of England.

In 876 under their new leader, Guthrum, the Danes slipped past the Saxon army and attacked and occupied Wareham in Dorset. Alfred blockaded them but was unable to take Wareham by assault. Accordingly, he negotiated a peace which involved an exchange of hostages and oaths, which the Danes swore on a “holy ring” associated with the worship of Thor.[citation needed] The Danes, however, broke their word and, after killing all the hostages, slipped away under cover of night to Exeter in Devon.

Alfred blockaded the Viking ships in Devon, and with a relief fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to submit. The Danes withdrew to Mercia. In January 878, the Danes made a sudden attack on Chippenham, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas, “and most of the people they killed, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney in the marshes of Somerset, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe”. From his fort at Athelney, an island in the marshes near North Petherton, Alfred was able to mount an effective resistance movement, rallying the local militias from Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire.

Alfred the Great is scolded by his subject, a neatherd’s wife, for not turning the breads but readily eating them when they are baked in her cottage.

A popular legend, originating from 12th century chronicles, tells how when he first fled to the Somerset Levels, Alfred was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn, and was roundly scolded by the woman upon her return.

870 was the low-water mark in the history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. With all the other kingdoms having fallen to the Vikings, Wessex alone was still resisting.

Counter-attack and victory

King Alfred’s Tower (1772) on the supposed site of Egbert’s Stone, the mustering place before the Battle of Edington.

In the seventh week after Easter (4–10 May 878), around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to ‘Egbert’s Stone‘ east of Selwood, where he was met by “all the people of Somerset and of Wiltshire and of that part of Hampshire which is on this side of the sea (that is, west of Southampton Water), and they rejoiced to see him”. Alfred’s emergence from his marshland stronghold was part of a carefully planned offensive that entailed raising the fyrds of three shires. This meant not only that the king had retained the loyalty of ealdormen, royal reeves and king’s thegns (who were charged with levying and leading these forces), but that they had maintained their positions of authority in these localities well enough to answer his summons to war. Alfred’s actions also suggest a system of scouts and messengers.

Alfred won a decisive victory in the ensuing Battle of Edington which may have been fought near Westbury, Wiltshire.

The Saxon Chronicle records: “Fighting ferociously, forming a dense shield-wall against the whole army of the Pagans, and striving long and bravely…at last he [Alfred] gained the victory. He overthrew the Pagans with great slaughter, and smiting the fugitives, he pursued them as far as the fortress [i.e., Chippenham].”

He then pursued the Danes to their stronghold at Chippenham and starved them into submission. One of the terms of the surrender was that Guthrum convert to Christianity. Three weeks later the Danish king and 29 of his chief men were baptised at Alfred’s court at Aller, near Athelney, with Alfred receiving Guthrum as his spiritual son.

The “unbinding of the chrism” took place with great ceremony eight days later at the royal estate at Wedmore in Somerset, after which Guthrum fulfilled his promise to leave Wessex. The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, preserved in Old English in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (Manuscript 383), and in a Latin compilation known as Quadripartitus, was negotiated later, perhaps in 879 or 880, when King Ceolwulf II of Mercia was deposed.

That treaty divided up the kingdom of Mercia. By its terms the boundary between Alfred’s and Guthrum’s kingdoms was to run up the River Thames, to the River Lea; follow the Lea to its source (near Luton); from there extend in a straight line to Bedford; and from Bedford follow the River Ouse to Watling Street.

In other words, Alfred succeeded to Ceolwulf’s kingdom, consisting of western Mercia; and Guthrum incorporated the eastern part of Mercia into an enlarged kingdom of East Anglia (henceforward known as the Danelaw). By terms of the treaty, moreover, Alfred was to have control over the Mercian city of London and its mints—at least for the time being.[19] The disposition of Essex, held by West Saxon kings since the days of Egbert, is unclear from the treaty, though, given Alfred’s political and military superiority, it would have been surprising if he had conceded any disputed territory to his new godson.

A coin of Alfred, king of Wessex, London, 880 (based upon a Roman model).

With the signing of the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, an event most commonly held to have taken place around 880 when Guthrum’s people began settling East Anglia, Guthrum was neutralised as a threat. In conjunction with this agreement a Danish army left the island and sailed to Ghent.

After the signing of the treaty with Guthrum, Alfred was spared any large-scale conflicts for some time. Despite this relative peace, the king was still forced to deal with a number of Danish raids and incursions.

Further Viking attacks repelled (890s)

After another lull, in the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again. Finding their position in mainland Europe precarious, they crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body at Appledore, Kent, and the lesser, under Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from which he could observe both forces.

While he was in talks with Hastein, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck northwestwards. They were overtaken by Alfred’s eldest son, Edward, and were defeated in a general engagement at Farnham in Surrey. They took refuge on an island at Thorney, on Hertfordshire’s River Colne, where they were blockaded and were ultimately forced to submit. The force fell back on Essex and, after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, coalesced with Hastein’s force at Shoebury.

Alfred had been on his way to relieve his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter and an unnamed stronghold on the North Devon shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and raised the Siege of Exeter. The fate of the other place is not recorded. Meanwhile, the force under Hastein set out to march up the Thames Valley, possibly with the idea of assisting their friends in the west. But they were met by a large force under the three great ealdormen of Mercia, Wiltshire and Somerset, and forced to head off to the northwest, being finally overtaken and blockaded at Buttington. Some identify this with Buttington Tump at the mouth of the River Wye, others with Buttington near Welshpool. An attempt to break through the English lines was defeated. Those who escaped retreated to Shoebury. Then, after collecting reinforcements, they made a sudden dash across England and occupied the ruined Roman walls of Chester. The English did not attempt a winter blockade, but contented themselves with destroying all the supplies in the district. Early in 894 (or 895), want of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex. At the end of this year and early in 895 (or 896), the Danes drew their ships up the River Thames and River Lea and fortified themselves twenty miles (32 km) north of London. A direct attack on the Danish lines failed but, later in the year, Alfred saw a means of obstructing the river so as to prevent the egress of the Danish ships. The Danes realised that they were outmanoeuvred. They struck off north-westwards and wintered at Cwatbridge near Bridgnorth. The next year, 896 (or 897), they gave up the struggle.